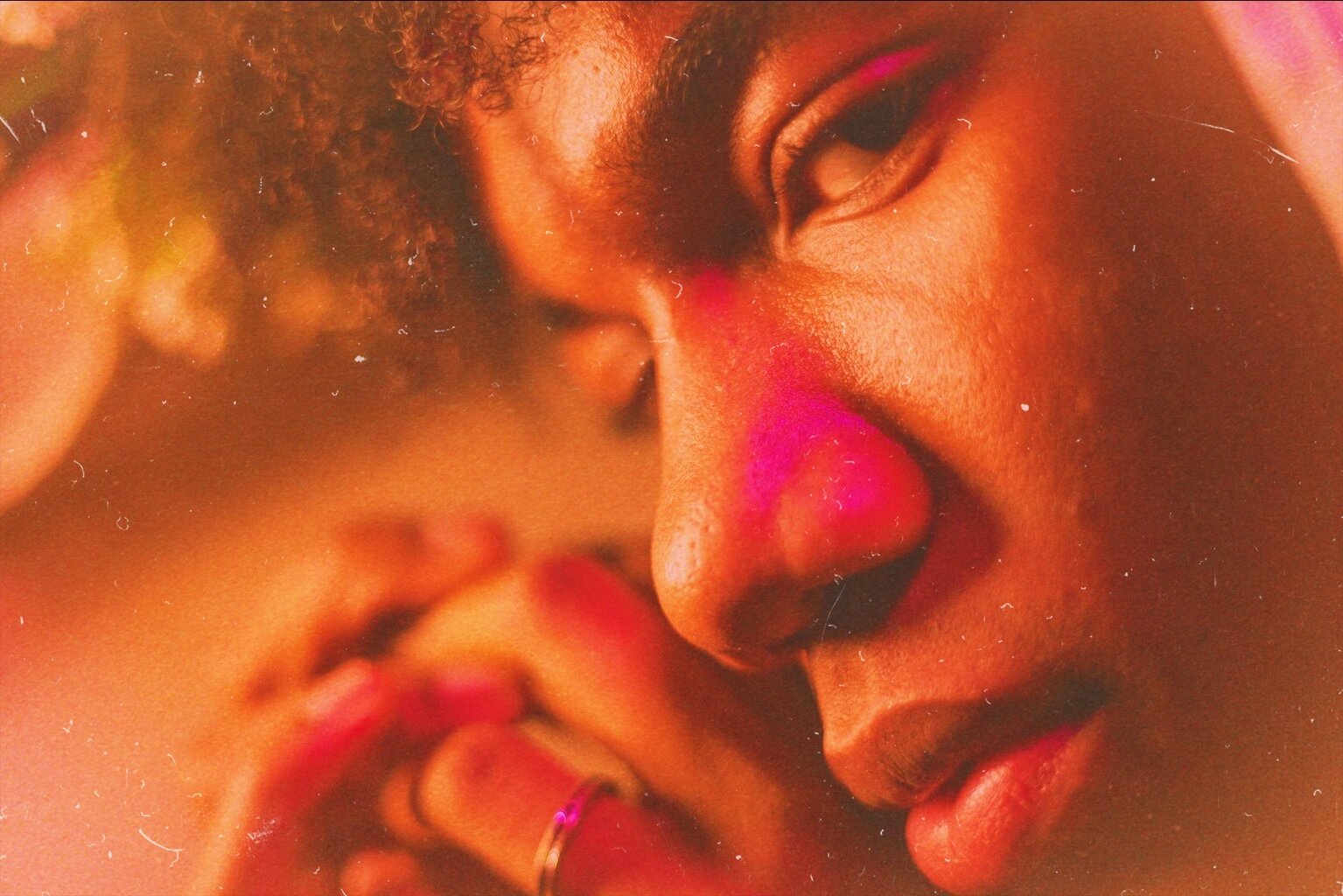

Jabari Courtney (left) and Tyler Bey (right)

Let me start by saying this: there is an absolute distinction between healthy expressions of black masculinity and the toxic perpetuations of hypermasculinity that drive male suicide, domestic violence, and gender inequality issues within the black community. One of these things deserves to be uplifted and celebrated, and one demands to be deconstructed and analyzed, traced to its core and examined for the cure to it’s deadly plight. Toxic masculinity is a plague to men and functions as a mechanism in a larger system of patriarchy within society. Through its deconstruction, we can highlight and celebrate diverse forms of masculine expression not prescribing to stereotypes and gender expectations. In the context of an emerging generation of young black men navigating adolescence and identity in 2019, we examine how the black masculine image can take many forms, and present radically different from hypermasculine stereotypes.

Visually, we strived to explore the land within where emotions and complexities dwell — things men are often told to hide or suppress. The art that is the black male image can be drawn in many forms. Within there dwells an intangible sea where their emotions rise and fall like saturated tides reflecting sunset. Through dialogue and conceptual portraiture, Jabari Courtney and Tyler Bey visualize and discuss the image and interpretations of black masculinity, its distinction from more toxic expressions of it, and the detriment hypermasculinity can have to the community on a whole. And through our endeavour of deconstruction, we present an image of black men that reflects the emotive vibrancy and nuance that are neglected in perpetuated portrayals of hypermasculinity.

Erin Davis for Pink Things: What is your interpretation and experience with masculinity? What does it mean to you to be masculine? What does it look like in both behavior and appearance/function?

Jabari Courtney: Well for me, my new definition of masculinity is about physical and mental strength. Not necessarily like “Oh, you have to be the strongest person out there,” but there is a certain physical aspect to masculinity and then there is a certain mental aspect. I used to think it was about who was biggest and strongest. But it's more about all that you can do to contribute and help those around you. When I was younger, masculinity seemed more representative of who played sports and who had the best clothes, but masculinity is more about who is a supporter and contributor.

Tyler Bey: The way we think about fashion and art — they’re mostly just ways we express ourselves and not how we necessarily identify, because that may change over time. And I think that’s the beautiful thing about masculinity. It doesn’t have to stay the same, it changes with time, whether that be on a personal level or on a grander level. With that comes your own choice in what it will mean to you.

Tyler Bey

Pink Things: Tyler, you approach masculinity in a way that’s interpretive and ever-evolving. That’s interesting, and the distinction between healthy expressions of masculinity and toxic masculinity is important. There are so many ways to appreciate masculinity without feeding into toxic ideas. How do you think ideas of masculinity can turn toxic?

TB: Well, I think the main problem is we live under a patriarchy; everything is viewed through the lens of what men desire and what is important to men. And when you look at it through that lens, everything that masculinity means can become negative. When you think of our perception of men, you think of the muscular nature, sex, and sexuality — when you look at these through that patriarchal lens, everything needs to be bigger and stronger. If you’re not a certain way, you’re not masculine enough. Masculinity is put into a box, and when you try to define what it means for everyone, that’s when the toxicity comes into play.

JC: When I think of toxic masculinity, I think of heteronormativity — who can get the most women, who has the best clothes, or is the most attractive. When you’re a gay dude, people feel that you can’t also be masculine. But your sexuality has nothing to do with your masculinity. Most people think you can't be a gay person and masculine because of how the media infuses it with feminine traits. Femininity and masculinity are two different things. Some people feel that if you have some feminine traits, you can’t also possess masculine ones. They are just two different ideas surrounding two different “genders”. To me feminity is equal to masculinity in that it’s something that can uplift and support people. But as people view it in society, if you display traits of femininity, you’re not masculine. And then that goes back to sexuality, because if you’re a dude who likes dudes, that’s interpreted to be feminine so people strip you of your masculinity. And that is where I think toxic masculinity comes in.

Jabari Courtney and Tyler Bey

PT: When we try to take something that’s so diverse and multifaceted and nuanced and shove it into a singular box, that’s when narrow minded ideas really come into play. And these ideas have just as much potential to hurt men as much as they do women. What do you think about that?

TB: In my experience, when you feel that you have to meet a certain expectation, there are two outcomes that occur: you either chase that idea that you will never reach, or you will damage yourself and the people around you in the effort of being verified or validated by society’s interpretation of masculinity. If you deviate from that it can cause inherent isolation and loneliness because you’re not a part of the masculine circles; you’re not invited to those football and basketball games; you're not a part of that clique. But you can also find your own healthy balance in saying, “No, I don’t want to be like you because I can be enough by myself and I don’t have to conform to your rules, yet I can still be a part of your group.” These are middle grounds, but we live in a very extreme world where you’re either with someone or you’re against them. Cancel culture really dives into that. But everything can have middle ground, and in masculinity you can still have those hypermasculine friends without perpetuating it on an individual level.

PT: And how do you express your masculinity individually? How does it make you feel?

TB: I express my masculinity by staying true to myself and by trying to show more diverse depictions of men through my own artwork, my theatre, my writing; by being the example of the black man I needed for myself.

PT: Can you tell me a bit about your thoughts on and experiences with hypermasculinity in the black community?

JC: I deal with it every day. I go into situations where it is something as simple as talking — like, I am not a sports person. So when I go up to another black dude and the conversation of sports comes up and you can't talk about it, I feel like it's a point deducted from your masculinity. It's things like that in the black community, especially considering things like barber shop culture. It's like, there are these ideas and if you don't believe in them you're not masculine. For instance, a lot of people in the black community who aren't very progressive think that if you support gay rights then you're automatically not a real man.

Jabari Courtney

PT: I think it is really interesting that we keep coming back to sports as a metaphor or visualization of black masculinity, especially in the context of it being a way black people are able to uplift themselves and break cycles of poverty; relying on sports as a way out of challenging socio-economic situations. But also, athletes, entertainers, they are all notoriously exploited by the people that give them those contracts — it’s more of a way of coming up within the system without ever leaving it.

JC: Yeah. Growing up, sports was really a main factor of masculinity; like basketball, football. When I think of masculinity, I always think of that.

Tyler Bey

PT: I would love to know your thoughts on how you think hypermasculinity affects and impacts black youth.

TB: I really see a lot of this at my school where the connection between hypermasculinity and what it means to be a man affects the value of getting an education and respecting women, adults, and teachers. None of it is to our benefit. So while we think we are “the shit” by doing things we think give us power — illegal things, violent things, things that we feel we have to do to be a man — none of it is ever helping us individually, or in the long run for our community.

PT: How has hypermasculinity affected you emotionally or in your thoughts on a personal level?

JC: It used to make me feel like I was less of a person because I didn’t fit the image of what a masculine black man looks like. So, even around other dudes my age, I felt very self-conscious about who I was to the point where I felt that there was something wrong with me. It really made me feel like I wasn't equal to the other black guys my age. But as I got older, I realized that hypermasculinity is not the requirement. It’s just a small part of life when you look at the big scheme of it all.

PT: And what do you think contributes to hypermasculinity in the black community? What negative mental effect can this have on young black men?

JC: Tradition. In the black community there are traditions where, you know, black girls do this and black boys do this. Personally, not fitting in with that made me feel as though I had less value in comparison to the other guys. Even growing up, everything was about masculinity and if you couldn’t do things that were viewed as masculine, you were thought of as less.

PT: A common theme is that hypermasculinity is not the equivalent of masculinity and just because you’re not hypermasculine doesn't make you feminine. When you think of the stereotypical hypermasculine black male image, a specific image often comes to mind: over sexualised and influenced by stereotypes. This is not created or promoted by black people and it has a lot of racial undertones to it. A lot of the time, the general perceptions people have about black people aren’t actually created by black people. Hypermasculinity for black men is often interwoven with racism. And it can really hurt the community.

TB: And we end up just feeding into it ourselves while simultaneously saying, “Black and beautiful and proud.” But when you feed into these systems made by white people, it’s counterintuitive.

PT: And how have these images and ideas of hypermasculinity affected you emotionally or mentally?

TB: So I’ve already mentioned the inherent loneliness — like there’s a point when you decide, “No, I don’t want to feed into this stereotype about men,” that you want to be different. Initially I did find myself to be quite lonely because I would look outside and see all the sports I wasn’t interested in or apart of. Sports alone are a big part of hypermasculinity. But I would mostly just be watching all the boys and I didn’t feel I could talk to them. For instance, with my dad, he was not around in my life and I think not having some sort of positive masculine arrow to point me in the right direction left me aimless and afraid. I have memories of being afraid of black men. A part of this was my fault because I didn’t realize the middle ground was an option instead of a hard cut off; thinking that being friends with boys wasn’t for me because I felt that no matter where I was, I would not fit in. That led to me being afraid of my own uncles and being afraid of men, being afraid of black men, not knowing how to really talk to men, only having friends that were girls and women. I really regret that part of my life where I was just confused about what it meant to be a man and not knowing that I can make friends and live my life as a boy and not feel like I have to succumb to hypermasculinity pressure.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

All photos by Erin Davis.

Erin Davis is a writer, artist, photographer and multimedia journalist based in Atlanta. She is a regular contributor for Pink Things.